I was talking to a friend about this the other day, saying that it was one of the aspects of genre fiction that always appealed to me: that it is in children’s fantasy and science fiction (and by children, I mean what publishers call “young adults,” as well) that I found strong, independent girl protagonists.

And that’s essential for the development of a bookish girl, one who might be a feminist without really knowing at that stage what feminism entails.

Of course, the same is true for boys: if they’re fantasy readers, they need to see characters who aren’t just psychopaths with swords. And readers of both genders need to see strong characters of the opposite gender. So the point I’m trying to make here is not intended to be sexist or exclusive in any way.

But I’m more interested here in the girls of fantasy and science fiction, not least because of the point I’m about to make.

Successful film and television franchises tend to bring these books to new audiences. But when the books are filtered through other forms of media, characters who are or have been socially marginal often suffer. And it’s not just female characters, of course: think of the “whitening” of Ursula Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea.

But the books are always there, no matter how manipulated, how poor, or how plain different the films might be.

So I’ve compiled a list, in nor particular order, of some of my favourite strong girls from children’s fantasy and science fiction—and I’ve left out Baum’s Dorothy (about whom I have written elsewhere on this blog) and Carroll’s Alice (about whom cleverer people than I have written).

It was going to be just a bullet-pointed list, but then I started writing more and more about the first girl on the list, and I thought, “Well, I haven’t bored people with a series in a while.”

So now it’s a series, the first part of which looks at Laura Chant, in New Zealand author Margaret Mahy’s The Changeover (1984).

This is the book that started the discussion I mentioned above: I’d never read it—though I have a feeling that I might have read other Mahy books, in my dim and distant childhood—while my friend said that it was for her, as a child, the first book that made her feel she too could be powerful and achieve great things.

All that is centred on Laura Chant.

Laura exists in a world of dangers, but the dangers aren’t all magical or supernatural. Laura moves through a relatively small, relatively new suburb, one that exists in an uneasy state that we are still seeing in newer suburbs: bored teenagers, trapped by their youth and the comparative distance of the city—it’s always so far away, when one has no transport. (Running through this book, for example, is the younger teenager’s admiration for those older students who have access to their parent’s cars. The fact that a boy might be worth going out with just because he has access to his mum’s car is a moment that so effectively captures the spatial limitations of the teenage years.)

So the teens and the young men who can’t find employment despite the city’s growth gather in gangs, which may not intend violence but nevertheless present an implicit threat to those weaker or more liminal than the gangs themselves—especially when the situation does, on occasion, spill over into actual violence.

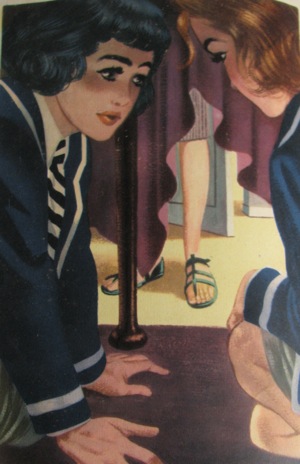

In one scene early in the book, Laura, walking through the suburbs at night, remembers these acts of violence, and moves along the edges of shadows, anxious not to put herself in plain sight or to step fully into shadow where others may be hiding.

This liminality is echoed in her age: fourteen, and still, she says, unfamiliar with the new body that has recently replaced her childish form.

It’s echoed in her appearance: she’s distinct from her blonde mother and baby brother since her genes, like those of her absent father, are paying homage to a Polynesian ancestor among her great-grandfathers.

It’s echoed in her position between the supernatural and natural worlds: she’s sensitive, but it’s not a power over which she has any control, and its manifestations only makes her feel more separate from everyday life, especially since it’s not an experience she can ever explain to anyone. She tries—unlike so many young girls in fantasies set in the contemporary world, she talks about her abilities. And people listen. But they can’t understand.

When it becomes apparent that her sensitivity could lead to more active powers, the experience of unlocking these is also evoked in terms of liminality: walking through a shadow of the world, she sees brambles that are also herself, and books that are also trees—or are the trees also books?

But her liminality is not weakness: she does walk through the night and she does walk through dangers—and though she says she’s uncertain of her new body, she holds herself intact and she holds her own, whether encounters are implicitly or explicitly threatening.

When, by the end of the book, she grows into the face (and the self) that was promised to her in the beginning, we are none of us surprised.