This is the post that I’d originally intended to write last night, before I became distracted and a little cranky.

This, though, is less ranty. This is a disconnected (though slightly less disconnected than last night’s effort) run through some of my favourite children’s books—only some, but there isn’t room for all of them.

Some of them, though, are not books that I re-read regularly. This one, for example, I haven’t read in years:

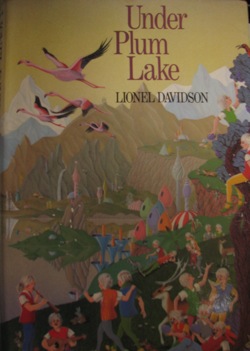

Looking the author up on Wikipedia, I discovered he apparently writes “acclaimed spy thrillers,” which makes this book—a strange fantasy in which a boy living in Cornwall begins to experience memories of living in the advanced, subterranean world of Egon—an even odder addition to his oeuvre.

When I did read, though, I loved it. The Egonians are significantly advanced, physically and mentally, compared to humans, but sometimes bring humans down into their world. When they return them, they replace their memories of Egon with false ones, so when the protagonist’s memories start resurfacing, he can initially make no sense of them.

I remember, too, a strange streak running under the story: the Egonians—whose awareness of their bodies is such that they can immediately sense when something is ceasing to work effectively—cannot feel pain, and their reactions to the inherent fragility of humans disturbed me somewhat as a child.

Perhaps I should re-read this one; it has been quite some years.

Or perhaps Lewis Carroll? But I’ve not included Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland or Through the Looking Glass here, though—as a good fantasy fangirl and researcher in Victorian fiction, I love them both.

But this is a far more anarchic work than either:

This, alas, is a cut-down version of Carroll’s original two volumes, Sylvie and Bruno (1889) and Sylvie and Bruno Concluded (1893).

The novels take place partly in a fairyland called Outland—where a revolution is underway to oust the Warden, Sylvie and Bruno’s father, and replace him with the tyrannical Sub-Warden—and partly in England, where the highly moral young doctor Arthur Forester is more or less successfully wooing Lady Muriel, daughter of the Earl of Ainslie. The two parts are linked by an unnamed narrator, suffering from an unidentified illness that Wikipedia suggests might be narcolepsy. (They don’t give their source, but it’s an interesting idea, given that the narrator regularly drops into dozes, in which he sees the fairy children.)

This cut-down edition only includes the Outland material, which seems distinctly counter to Carroll’s intentions. Unfortunately, the two novels are rarely reprinted, and this seemed a better cover to include than my Complete Works of Lewis Carroll, where I have the two novels in their complete form. Plus, I love the Harry Furness illustration on the front there.

The novels are odd ones; Carroll himself called them “litterature” (no, that’s not a typing error), according to this fascinating article from Tom Christensen’s Right Reading site. The temporal, physical, and narrative shifting from Outland to England; the long, intruded, moralising passages on inherited wealth, the affectations of High Church practice, or alternative ways of organising the animal kingdom; the highly sentimental plot with Arthur and Lady Muriel, their brief marriage, and Arthur’s eventual fate—all these confused me as a child-reader.

But I was fascinated by the books, nevertheless. And I remain fascinated with them, especially now I have a more thorough understanding of how Victorian literature shifts and develops.

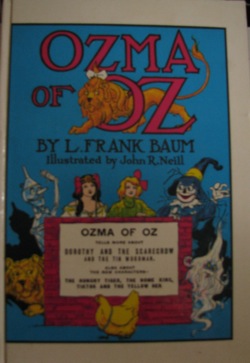

Or L. Frank Baum?

I’ve only bought this edition recently, actually, and now want to collect all of them in these facsimile hardbacks: I also have The Tin Woodman of Oz (1918) in this edition.

Ozma of Oz (1907) fascinates me: I’ve heard The Wizard of Oz (1900) called the first American fairytale (though I can’t remember where I heard that: if anyone knows, let me know so I can attribute it correctly), but the books seem to me to be analogous to Carroll’s Alice books, in one significant way: both books take a distinct step back from the standard Victorian model of immature femininity, of the angelic child, Dickens’s Little Nell or Stowe’s Little Eva.

Dorothy Gale—and, gradually, the other child-characters who are shifted from America to Oz, like Button-Bright, Trot, and Betsy—is, like Alice, unwilling to accept adult authority simply because it is adult authority, especially when the Wizard, like so many of the other authority figures, turns out to be a humbug.

Ozma of Oz was one of the books that inspired the 1985 film, Return to Oz and, while I know so many people hold the Judy Garland film dear, I much prefer the sequel, which seems to me truer to the nature of the books: terrifying, often cruel and arbitrary, and ultimately centred on the bravery, intelligence, and tenacity of a young girl.

Ditto George MacDonald:

There’s little, I suspect, that I can say about MacDonald that isn’t covered by the fact that his devotees include C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, and Madeleine L’Engle.

(Sadly, I haven’t included A Wrinkle in Time in this list, though I should have. Or the Narnia books. Or The Hobbit. There simply isn’t room for everything.)

At the Back of the North Wind seems to be the most frequently reprinted—and perhaps most frequently cited—of MacDonald’s fantasies, where others—such as The Day Boy and Night Girl (1882) or “The Light Princess” from Adela Cathcart (1864)—are rarely reprinted or re-read. But The Princess and the Goblin (1872) is by far and away my favourite, even more so than the sequel, The Princess and Curdie (1883).

On a slightly unrelated note, the other thing that intrigues me about George MacDonald is how much he looked like Rasputin. That’s one intense-looking writer of whimsical Scottish fantasy stories for children.

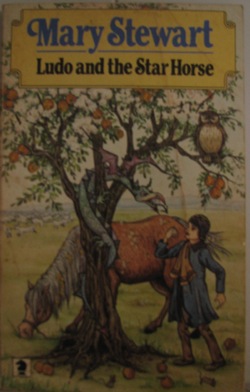

Do people still read Mary Stewart?

I have another of hers in the same series of reprints: The Little Broomstick (1971). Apparently, this, Ludo and the Star Horse (1974), and A Walk in Wolf Wood (1980) are her only children’s novels. I’ve never read the latter, but I adored the other two, especially Ludo, which tells the story of a young boy living in the Tyrol, who follows the family’s old horse (on which their livelihood depends) out into the snow one night, and ends up travelling with him through the land of the Zodiac.

Nick didn’t care for this book, at all, because it does have a melancholic ending. I still maintain, though, that it’s one of the most unusual fantasies I’ve ever read. (And, yet, part of the reason why I’m so fascinated specifically by children’s fantasy is because it’s often so innovative compared to fantasy novels written for adults.)

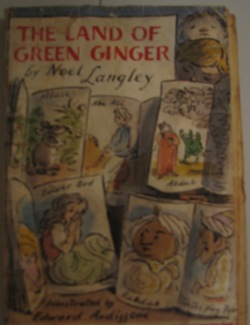

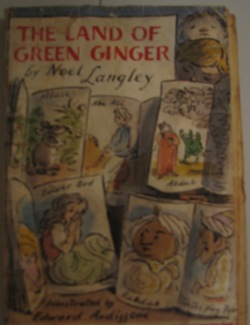

But I can’t end without this book:

This picture doesn’t do justice to how battered my poor copy of The Land of Green Ginger is. According to the Wikipedia page, it’s rarely been out of print since it was published in 1937, which doesn’t surprise me, except that I don’t think I’ve ever seen a copy in a bookstore or a booksale. If I had, I would certainly have bought one to sit alongside this beloved paperback, which is more sellotape than anything else.

No one’s bookshelf is complete without the adventures of Abu Ali (son of Aladdin, but too nice to be a satisfactory heir), Silver Bud, Mouse, Boomalaka Wee, and, of course, the Friend of the Master of the Horse.

I wish I had more room here. I haven’t mentioned Tove Jansson’s Moomintroll books, or Lucy M. Boston’s Green Knowe series, or Diana Wynne Jones (though no convincing is required there, surely?), or Mary Poppins, or the Wombles, or Helen Cresswell’s Bagthorpe Saga, or any of a hundred other fabulous children’s books.

But I have talked myself out of the cranky mood that Harold Bloom and A. S. Byatt put me in yesterday.

After all, I have all these lovely books. And no one can actually prevent me from reading them as often as I wish, whatever opinion they might subsequently entertain about my intelligence or my maturity.