Let Me Tell You How Much I've Enjoyed The Gallagher Girls

Posted 1 February 2010 in Books by Catriona

I know you’re dying to hear all about it.

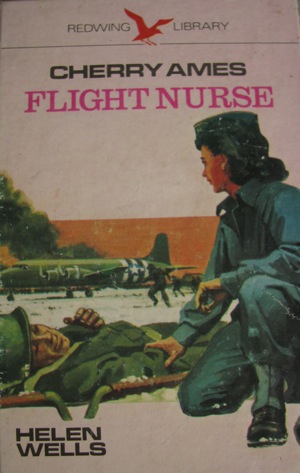

Because you know me, right? (And if not, if you’re new to the blog, hi!) You know there’s nothing I love more than a good girls’ school story. Remember how excited I was when I discovered there was such a thing as vampire boarding-school stories?

This is like that time, only with spies.

The Gallagher Academy for Exceptional Young Ladies is ensconced behind high stone walls, bears all the hallmarks of a posh private (or public, depending on where you’re reading this) school, even attracts the scorn of the town’s residents, who have perfected what the girls call the “Gallagher Glare” whenever they spot a student in the town.

But it’s a school for spies.

And it’s more than that: it’s a school for the daughters of American spies (and one girl whose parents are MI6, brought in at the discretion of the new headmistress). Some of the girls, the ones whose parents aren’t spies, have been brought in because of exceptionally high test scores, so, as far as their parents are concerned, they really do just attend a school for exceptionally bright students. But they’re training all the while for a future career in either the CIA or some other initialism-heavy organisation.

When I first thought about writing a piece on these books, I was thinking to myself, “It would be so easy to write one of those snippet reviews you find in the back of women’s mags. You’d just write, ‘Harry Potter meets Alias‘ and you’d be done.”

To some extent, that reading still feels accurate to me. These books are like Alias: the insane gadgets, the almost superhuman powers of the spies, the frenetic excitement of the job. And they are like Harry Potter, and not just because they’re set in a boarding school: there’s a point in the series when the focal character Cammie Morgan goes to CIA headquarters with her mother for a debriefing, and accesses the building through a hidden elevator in a department-store changing room. There are shades there, to me, of the way Harry Potter’s world existed alongside, beneath, above, or around our own, but never quite overlapped.

That delights me.

I don’t want spies to be sitting in rooms peering at computer monitors. I want them to be rappelling down the sides of buildings and if, like Michelle Yeoh, they can do it in high heels, so much the better.

Even the titles of the books delight me: I’d Tell You I Love You, But Then I’d Have To Kill You; Cross My Heart and Hope To Spy; and Don’t Judge A Girl By Her Cover. (Apparently, the fourth one will be Only the Good Spy Young.)

Oh, don’t look at me like that: you know I love a bad pun from the time I wrote that blog post on Wuthering High (and its sequels, The Scarlet Letterman and Moby Clique).

But I’m not actually here to talk about puns. I want to mention instead the complex and fascinating way that these books negotiate interpersonal relationships.

The books are, according to Amazon.com’s method of categorisation, aimed at nine- to twelve-year-old readers, and that feels about right: there’s no sex, of course (unlike the Vampire Academy books, which are designed for older readers) and precious little kissing. They’re also distinctly heternormative: there’s no indication that any of the girls are attracted to other girls.

That’s not unusual for mainstream books in the 9-12 age range, of course.

But it’s also a stance that’s somewhat problematised by the books’ genre. Girls’ school stories don’t seem to be able to just adopt an unproblematic heternormative stance. Stories from the original burgeoning of the genre (from around the 1920s to roughly the 1950s) are frequently subjected to a kind of nudge-nudge wink-wink re-reading that draws on any hint of suggestiveness in the stories—I’ve done this myself, of course.

Sometimes the stories themselves are suggestive, as in the case of one I read that was a long moral tale arguing against passionate friendships with someone of your own gender: I wish I could remember the title of that one.

Perhaps that explains why more modern variants on the girls’ school stories foreground the heterosexuality of the pupils? In the Trebizon stories, for example, the girls are all paired off with their equivalent in the boys’ boarding school down the road, and the teachers encourage them to socialise together.

That would never happen at Malory Towers.

What happens in the Gallagher Girls series, though, is that these girls, who have been ensconced in a girls’ boarding school for the final seven years of their schooling, have absolutely no idea how to relate to the opposite sex.

None at all.

How would they? The only members of the opposite sex they’ve met since they were twelve—really, around the time you really start noticing other people as sexually or proto-sexually attractive—have been their teachers.

Most of them don’t even have a parental relationship as a model, because their parents are, by and large, spies out in the field. They don’t head home to home-cooked meals, family conversation, trips out to the zoo or shopping expeditions—they spend Christmas helping their parents trail arms dealers on the other side of the world.

Take the heroine Cammie, for example. She doesn’t even know how her parents met: it’s classified. So when she does meet a boy, she has no idea how to get to know him, except to treat it as a mission: she constructs an elaborate legend, presenting herself as a home-schooled, highly religious girl with a cat called Suzie, and she sneaks out of the school every chance she gets to meet this new boy.

It’s more complicated for Cammie, of course, because she’s what’s known as a “pavement artist”: her job is to trail suspects invisibly, or as near to invisibly as she can manage. And she’s good, too, but once she becomes aware of boys, she becomes rather more ambivalent: when a cute boy tells her he’d never have noticed her, she knows it’s a compliment, and part of her takes it that way, but part of her is hurt, too.

Cammie’s determination to pursue a boy who can’t know the truth about her school terrifies the teachers, who go so far, in a later book, as to arrange an exchange programme so the students can interact regularly with boys their own age.

Sure, much of what I like in these books comes down to the pavement-artist heroine, attractive but untrustworthy hero, the spy gadgets, the rappelling, and the occasional Code Red that locks the school down when out-of-the-loop parents drop by unannounced.

But I like, too, the way in which the books recognise that interpersonal relationships are complicated even if you do have a camera in your wrist watch and comms in your fake crucifix.