Magical Mystery Bookshelf Tour Stage Five: Still In The Spare Room

Posted 31 July 2008 in Books by Catriona

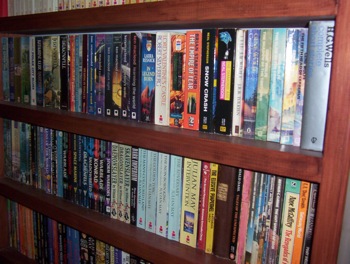

Honestly, it’s going to be a while before I’m finished with the spare room: there are still three (maybe three and a half, depending on how you count them) bookshelves to go, all much bigger than these two, and all stacked to within an inch of their lives.

On the plus side, this is the room in which I’m bound to find some interesting material: the situation is so dire in here, that I avoid pulling books off these shelves if I can, and tend to default to the more accessible ones in the living room and the hallway.

Really, maybe things are getting a little silly.

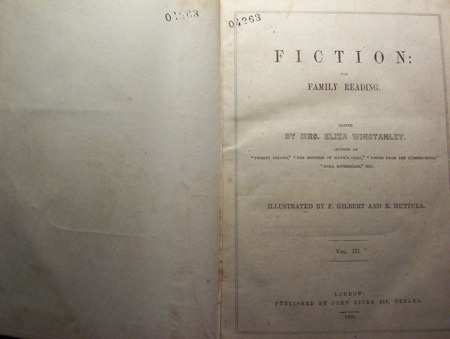

A case in point:

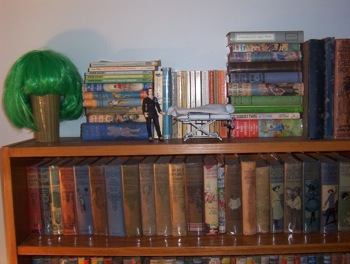

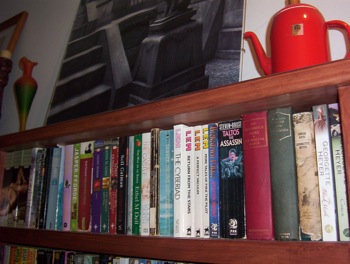

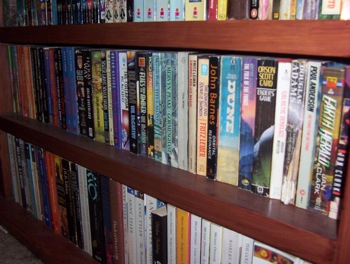

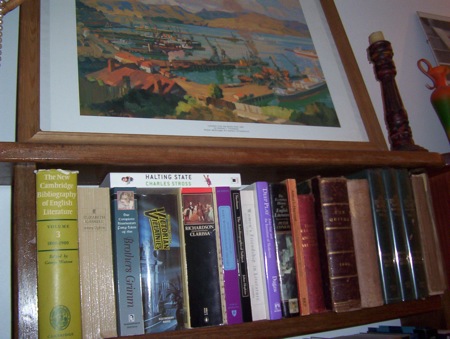

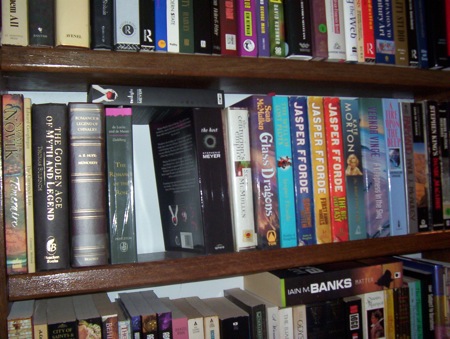

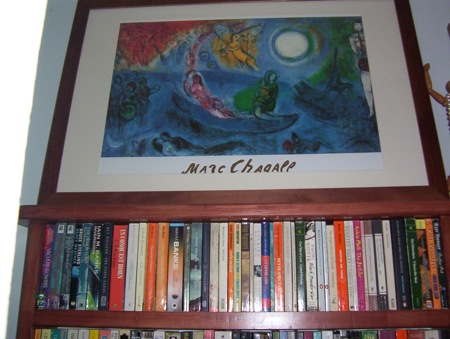

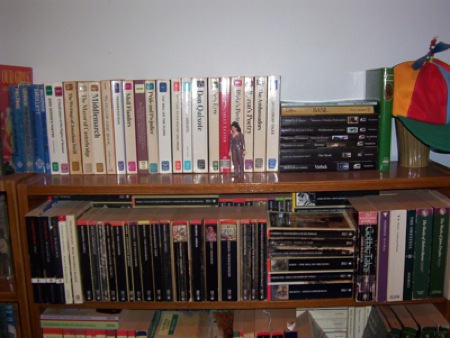

Oh, not the top shelf. Despite the fact that it includes a figurine of Deanna Troi in her embarrassingly unprofessional lavender number (Nick’s, I’m sure I don’t need to add) and a baseball cap with a propeller on the top (also Nick’s), this shelf is reasonably sedate. You can see the names of the books and everything!

I have a weak spot for Norton Critical editions, even though so many of these are rather old versions, which means their critical apparatuses—often written in the 1960s—are rather out of date in terms of current critical approaches.

But they’re so pretty! And their notes to the text are actually in footnotes rather than, as in Penguin and Oxford classics, endnotes, which means I can read the books without having to keep my finger in the back to hold my place.

On the other hand, that red book just behind Deanna is The Scarlet Letter, which I bought exclusively because I can’t resist a reasonably priced Norton Critical Edition, have never read, and may never read.

To balance that, though, eight books to its left, next to Moll Flanders (which I also haven’t read but may in fact own two copies of) is Frankenstein (the 1818 edition), which I’ve read multiple times. So it all works out even in the end.

(On the other hand, that book next to Frankenstein isn’t a Norton Critical Edition at all, now I look at it: it’s Andrew Lang’s Yellow Fairy Book, in a Dover reprint. That shouldn’t be there!)

That copy of Basil by Wilkie Collins—on the top of the horizontal books there—was one of my great finds of the last Lifeline Bookfest: it’s a Dover imprint. I do love Dover: they publish the most fascinating things, and they’re extremely readable editions. And under it is my little pile of Broadview Critical Editions. Broadview editions are fantastic: beautiful text and paper, gorgeous covers, clever and up-to-date critical essays. But they’re not cheap, and I only have the half-a-dozen. (Plus, one of those half-a-dozen books is yet another copy of Frankenstein, which is rather disturbing.)

I started this section with a point, didn’t I? Well, it’s more than could be expected for me to remember that for a fifteen-minute stretch at the end of the first teaching week of the semester.

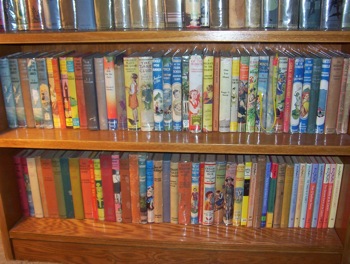

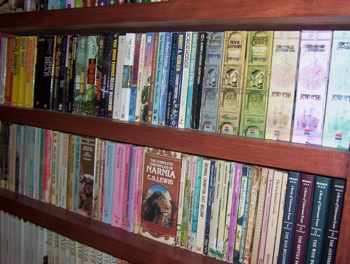

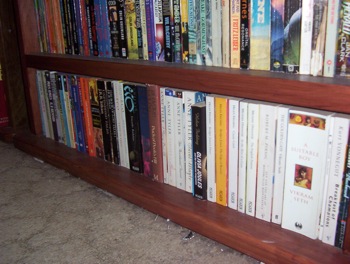

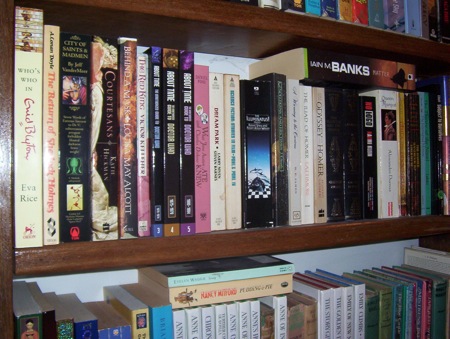

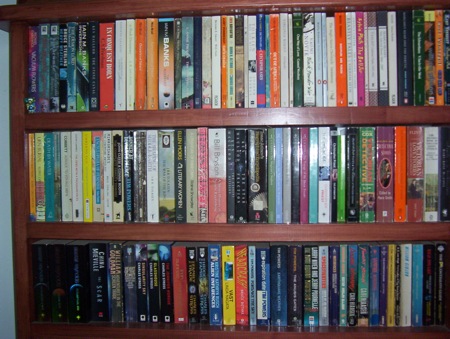

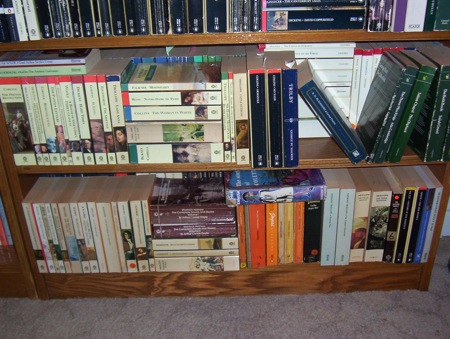

But my point was that the second shelf here really illustrates the problem with this shelf: the situation’s becoming increasingly absurd.

It only gets worse on the next two shelves:

Honestly, what’s the point of even putting books on shelves when you can’t get to them anyway? And the books at the front aren’t even the ones that I read most often—case in point: Thomas Carlyle’s The French Revolution on the far left, there—they’re just the ones that I’ve bought most recently. Or, in the case of Trilby, the ones that I’ve most recently moved off the bedhead where they’ve been languishing for many months.

(Actually, you know what’s really embarrassing? I’ve only just now come to the realisation that the only copy of Dangerous Liaisons that I own is a movie tie-in edition. Fair enough, it was a good movie. But when you own—and, miracle of miracles, have actually read—eighteenth-century French epistolary fiction, it’s best to own it in an edition that doesn’t have Glenn Close and John Malkovich on the cover. Really, I should read that again, though: that’s a brilliant book. I like the way De Laclos plays with the notion that correspondence is superficially transparent but actually opaque, explicitly intended for a single reader but actually easily transmissible. But that’s not important right now.)

(I seem to be thinking in asides tonight: another point that’s just occurred to me is that I really should pull Salem Chapel off this shelf, now I’ve reminded myself that it’s here, and read it. I’ve only just bought it, but I’ve been keen to read it for a while.)

(Note to self: blogs don’t really work when they’re stream of consciousness.)

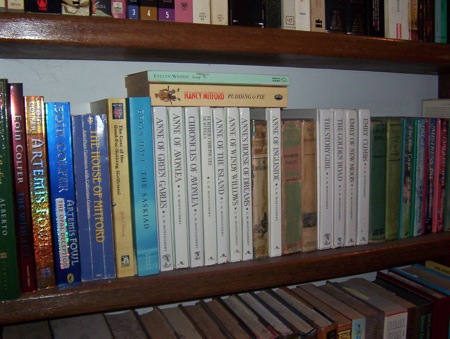

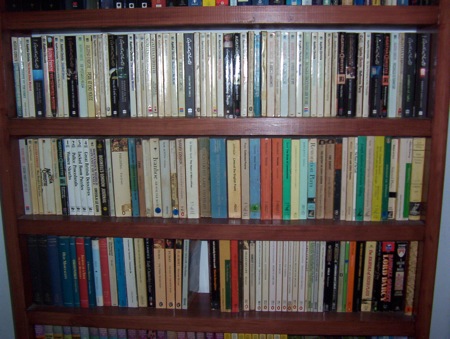

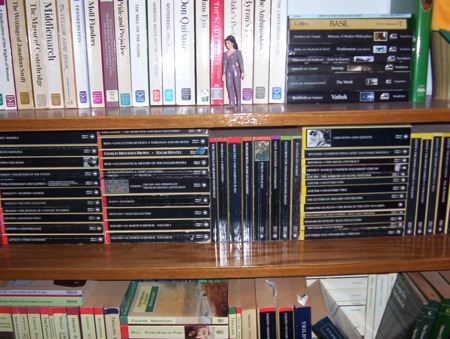

But when you pull the front row of books off the shelf, a miracle occurs:

Really, there’s nothing prettier than a row of Penguin paperbacks, is there?

(Although I mainly note, looking at this, that I don’t own enough purple Penguins (I think that one is Saint Augustine’s Confessions) and certainly not enough green Penguins (those two are Arthur Waley’s translation of Monkey, which I definitely need to re-read, and One Thousand and One Arabian Nights, which should be on everyone’s bookshelf. I don’t actually buy my books on the basis of their colour—well, not often—but it seems as though an absence of purple and green Penguins speaks to a corresponding absence in my knowledge of literatures other than those published in English and—if I’m to be entirely truthful—in England: as my point about The Scarlet Letter above probably showed, I’m woefully behind in my reading of classic American novels.)

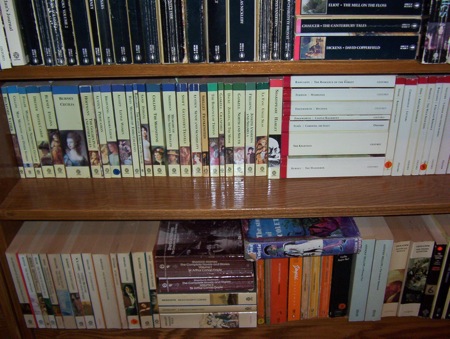

The only thing that might come close, pretty-wise, is a row of Oxford World’s Classics in paperback:

I vastly prefer the older Oxford editions with the cream-coloured spines and the broad coloured stripes to the modern white-and-red covers. Although this row just showcases the gaps in my organising principles: why are Fanny Burney’s Cecilia and The Wanderer at the back when her Camilla is at the front? That’s just odd. And, on that note, where is my copy of Evelina, the only Burney novel I’ve ever actually finished? Honestly, the point of this was to have a better idea of what I owned and where I had stored it. (Well, that, and to give myself an excuse for talking endlessly about books. As though I needed an excuse.)

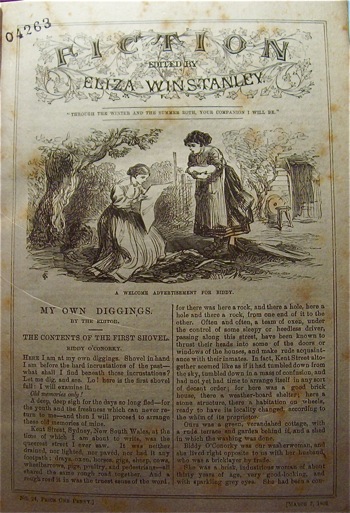

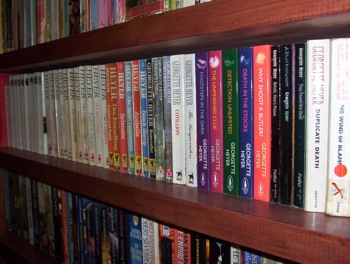

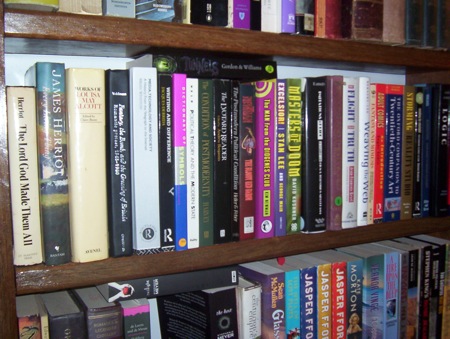

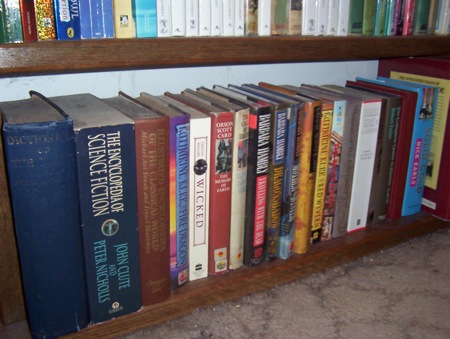

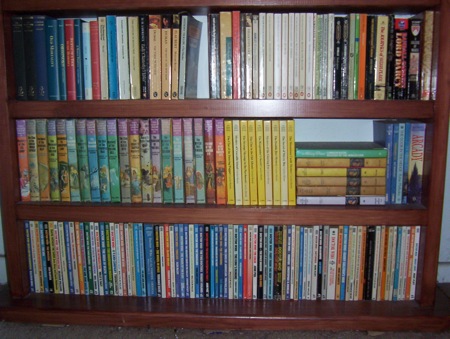

Oooh, actually De Laclos isn’t the most embarrassing book on my shelf:

That’s right: I have a television tie-in copy of Middlemarch. But I have two points to raise in my own defense, here.

Firstly, I do own another copy of Middlemarch.

Secondly, it’s got Rufus Sewell on the cover. Seriously: Rufus Sewell. It would take a stronger woman than me to get rid of that.

But, hey: at least I vacuumed the carpet this time.