Magical Mystery Bookshelf Tour Stage Two: Still The Hallway

Posted 4 July 2008 in Books by Catriona

Don’t worry: you can still skip over these posts if they become too boring. But I have tried harder this time to make the title of the books visible, which—whether my purpose is solipsistic or practical—seems a key concern.

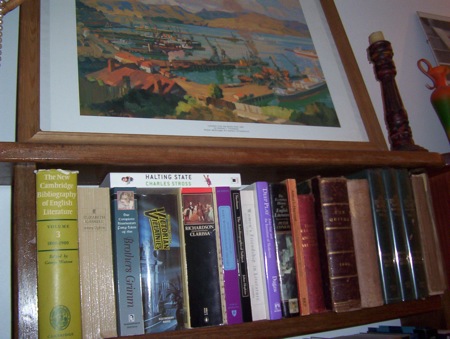

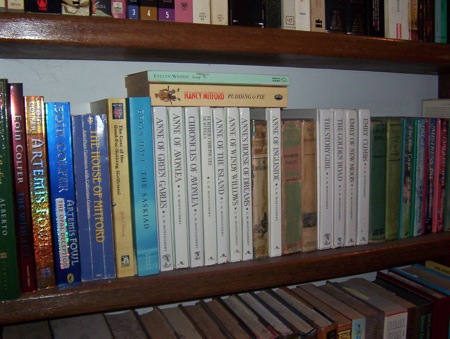

Mind, the pictures in this case are on a funny angle, because this is the middle bookshelf in the hallway, and I couldn’t get far enough back from the shelves to take a straight shot. But, really, it all adds an illusion of artiness to the project.

This is the most recent of the shelves, which Nick’s father made over the last Christmas holidays. I think it was this past Christmas, anyway. It had to be made narrower than the others so that all three would fit in the hallway without blocking any doorways (which didn’t bother me, but Nick claimed would be highly inconvenient).

Oddly, it was only after this shelf went in that I told Nick that I was slightly worried that the house was starting to look like a slightly disreputable secondhand bookshop. (It’s odd, because prior to that I’d always secretly hoped that the house would one day look like a disreputable secondhand bookshop.)

The painting on the top of this bookcase is a print of one of Sydney Lough Thompson’s paintings; he was a New Zealand-born Impressionist, and also Nick’s great-grandfather. Coming as I do from a line of anonymous peasants, I find it quite fascinating that Nick’s great-grandfather has his own Wikipedia page. (I mean, sure, it’s Wikipedia. But it’s still cool.)

(In case anyone is really interested, some of his paintings are here, although the site’s in French, and—even more astonishing to me than Wikipedia—there’s even a Youtube video, also in French but with some nice images of his works. See, the blog is educational!)

I’ve managed to retain most of this shelf, although that is Nick’s copy of Charles Stross’s Halting State lying horizontally up there—horizontal books on these shelves are a sure sign that space is desperately short elsewhere.

The copy of the Brothers Grimm I bought down in Sydney as a necessary tool for the thesis. I mentioned back in March that I ended up with multiple copies of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales: the Grimm tales were part of the same process, in that my author also rewrote several of these tales for her own journal. But the tales that she chose were fairly obscure ones, often not reprinted in incomplete collections, so I bought this complete edition. It’s good to have on the shelf, but it never actually made it into the bibliography for the Ph.D.; I defaulted to a late-Victorian translation by Margaret Hunt that I found on Project Gutenberg, as a more contemporary version of the tales.

How cool is The Cambridge Bibliography of English Literature, though? Everyone should have this on their shelf! No, seriously. Of course, this isn’t the most recent edition, but it’s still a fairly comprehensive survey of a wide range of authors.

It would also make a useful doorstop, if I were inclined to treat books in such a cavalier fashion.

But the books on this shelf that I love the most are those three slim, green volumes on the right: those are volumes seven, twelve, and fourteen of All the Year Round, conducted—as they point out on the spine, and the front cover, and the title page, just in case you didn’t see it the first two times—by Charles Dickens. Actually, all the volumes at that end of the shelf are Victorian periodicals, but these are the most exciting. Because of Charles Dickens, really.

Certainly, it’s far from a complete set—though I hope to pick up more in time; I bought these ones at the wonderful Berkelouw’s Book Barn in Berrima, the most alliterative antiquarian bookshop in Australia—but they’re fascinating. Volume 7, for example, has the fabulously titled “The Wicked Woods of Tobereevil,” by the Author of “Hester’s History” (seemingly, based on a quick Google search, by a woman called Rosa Gilbert, but don’t quote me on that) while volume 14 has “A Charming Fellow” by Frances Trollope. I could go on, but I won’t—I just never cease to be fascinated by how inexpensively one can buy some Victorian periodicals (although I did just pay a lot more than I did for these for a pair of much rarer volumes. But that’s another story).

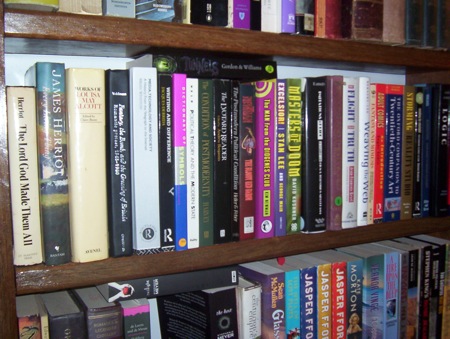

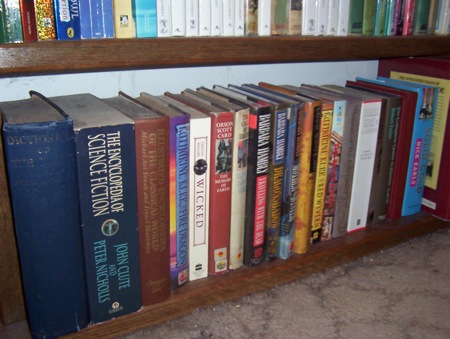

Frankly, the first thought that springs to mind when I look at this shelf is a sense of surprise that I own two hardback James Herriot books. He’s a fun read, especially in the early days, but I didn’t think I bought him in hardback.

Most of these are Nick’s books, though—including the rather embarrassing Masters of Doom, although I admit that I did buy that for him. But there’s Tunnels: since I’ve written not one but two posts on that book, it seems only fitting that its picture should turn up on here at some point.

And I do love that Louisa May Alcott hardback: it’s mostly short stories, which I hadn’t read before. Some of them, of course, are intensely saccharine; I imagine that they were originally written for children’s periodicals or Christmas giftbooks and, while Alcott never patronised her child-readers, she did write some intensely sentimental works. Still, I’ve always loved Little Women—though the final book, Jo’s Boys, both bewildered and devastated me—so it’s delightful to come across a whole pile of her works that I’d never read before. Another Lifeline Bookfest find, of course.

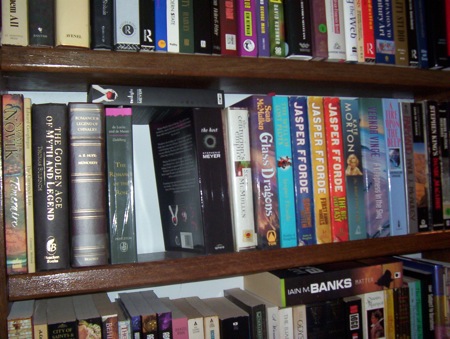

Hey, Jasper Fforde! I love those books—and he’s so prolific, there’ll probably be another out before long. But those are exactly my cup of tea, and I’ll keep reading them as long as he keeps writing them. They remind me—in a circuitous fashion—of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, but with less sex.

(Mind, Nick and I were watching Press Gang recently, and in the episode “UnXpected”—which deals with the illness of an actor who once starred in a Doctor Who/James Bond-style TV show—the character explains that he once spent two weeks inside The Hound of the Baskervilles thanks to a “fictionalising ray” but he escaped with another minor character. When the man he’s talking to says, “There’s no character of that name in Hound of the Baskervilles!” he urbanely responds, “Not now.” Nick turned to me and said, “Hang on, did Steven Moffat just invent Jasper Fforde?”)

I’m going to skip over everything else on this shelf (I’ve already expressed some concerns about the Twilight series, twice) except to note that I’m fairly certain that’s my copy of Bullfinch’s Mythology over there on the left.

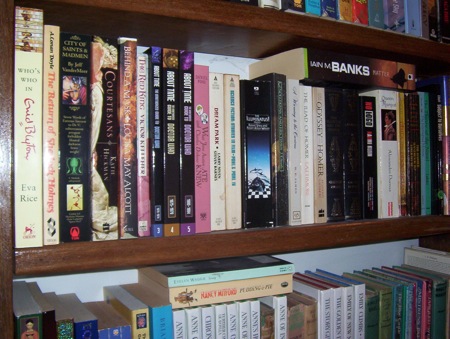

Ah. No, that’s not a book called Who’s Who in Enid Blyton. It’s some sort of highly specific mirage. No, honestly.

On the other hand, that book next to the mirage is a gorgeous facsimile reprint of the stories from The Return of Sherlock Holmes as they appeared in The Strand Magazine. I’m a sucker for facsimile reprints, but the loveliest ones—a growing collection of Victorian and Edwardian children’s fantasy novels—are in the living room.

I also find that collection of Alcott’s sensation fiction two books down from the Conan Doyle absolutely fascinating: I know Alcott herself was rather ashamed of her “pot-boilers”—as was Jo March, in Good Wives—but they’re good sensation narratives, and a far less idyllic account of the opportunities available to women than the Little Women series is.

Oh, dear: I seem to have truncated Alberto Manguel’s A History of Reading. That’s a shame. That’s the book that taught me that the ancient Sumerians—to whom I once referred as “Numerians,” to which my brother responded, “I suppose they were very good at arithmetic?”—called librarians “Ordainers of the Universe.” I have aspired to that title ever since.

I think that’s a complete set of L. M. Montgomery, too, although I may be lacking some of the short stories. The Anne books do get rather irritating after a while, but Anne of Green Gables remains utterly delightful every time I read it. And down towards the end is a copy of The Blue Castle: I never read that as a child, not until I bought it (at, surprisingly, the Lifeline Bookfest) a couple of years ago, and was quite astonished. It’s a fairy tale, of course, with a happy marriage to end things, but the fascinating aspect of it is the monotonous horror of the heroine’s early life—the sheer drudgery of being poor but of “good family,” thoroughly devalued for being an unmarried woman in a family that sees spinsterhood as the ultimate failure, unable to do anything independently, not even reading. It’s devastating, in a way.

But then Montgomery is often most interesting in the back stories of minor characters and in short stories: the women with illicit sex lives, with illegitimate children, with dark secrets. Little of this comes through in her best-known works, but some of the short stories show a much darker side to late-Victorian and Edwardian life than you’d ever imagine from the Anne books.

I’ve become overly prolific in my love of books, again—but I should point out Nick’s pride and joy, The Encyclopaedia of Science Fiction. He’d wanted it for years, but baulked a little at the price. I found that one in a Lifeline store in Narellan for $5, and thus cemented my position as best girlfriend ever.

$5 is a small price to pay for such a honour.

Share your thoughts