Bow Bells Novelettes

Posted 24 November 2008 in Books by Catriona

Look what just arrived in the mail!

I found this via the fabulous (and likely to bankrupt me) American Book Exchange, further via (if there is such a thing) the awesome BookFinder.

Actually, it’s lucky I don’t have a credit card: Nick is willing to use his, but far less susceptible to the charms of late-nineteenth-century serial fiction than I am, so he’s talked me down from more than one extravagant purchase.

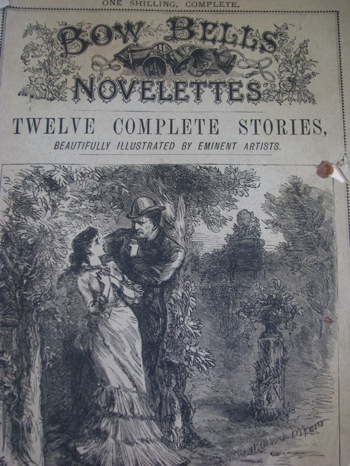

Not this this was extravagant: far from it, considering that it’s still in its original paper cover:

You don’t find that very often. Of course, the front cover has completely separated from the spine, for which I blame the postman—who curled the parcel up and shoved it between the letterbox and the fence paling. Why?—but then that’s not only reparable but also the downside of Victorian paperbacks. Yellowback collectors have been complaining for years about the relative fragility of the books and, in fact, they tend to be bought for their appearance only: they’re hard to read without damaging.

I didn’t buy this purely for decoration: more as a research tool, if I continue to focus on ephemeral nineteenth-century publishing, which I may well. But I’m certainly not planning to read it in bed.

And now, some context.

Bow Bells Novelettes was conceived by John Dicks as a spin-off to the highly successful Bow Bells, a penny weekly: that is, an inexpensive magazine published weekly, specialising in (largely lurid and melodramatic) fiction, and aimed at the working classes (though almost certainly read into the middle classes, as well).

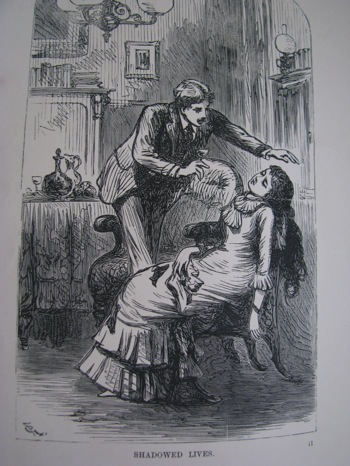

In my thesis, I dealt with Bow Bells Novelettes in the same chapter as Bow Bells itself, partly because Eliza Winstanley didn’t publish many stories in the former—not ones that I could confirm as hers, anyway—and partly because there’s not much distinction between the two journals, except that the stories in Bow Bells Novelettes are longer: each issue contains one “novelette,” a (generally) sixteen-page story, complete with three illustrations, like this one:

(That one looks to me as though it is by Frederick Gilbert, who did a great deal of illustration work for John Dicks’s publications: he was the less famous and less successful brother of Sir John Gilbert) who also did magazine illustration—most notably for The Illustrated London News and, I believe but I’d have to check, later for The London Journal under George Vickers—but was also a Royal Academician. Also, I genuinely made that decision on aesthetic grounds before I noticed the “FG” in the corner. Honestly.)

John Dicks’s publications achieved some notoriety at the end of the nineteenth century (separate from the type of notoriety attracted in the mid-nineteenth century, when G. W. M. Reynolds was editing Dicks’s publications) as the type of pernicious reading material likely to corrupt the working classes. In George Moore’s Esther Waters (1894), for example, we know that Esther is likely to find trouble in her new situation (she is eventually seduced by a fellow servant and abandoned while pregnant) because of the porter’s reaction to the books he carries from the station for her:

Sarah Tucker—that’s the upper-housemaid—will be after you to lend them to her. She’s a wonderful reader. She has read every story that has come out in Bow Bells for the last three years, and you can’t puzzle her, try as you will. She knows all the names, can tell you which lord it was that saved the girl from the carriage when the ‘osses were tearing like mad towards a precipice a ‘undred feet deep, and all about the baronet for whose sake the girl went out to drown herself in the moonlight. I ‘aven’t read the books mesel’, but Sarah and me are great pals.

(George Moore’s Esther Waters. 1894. Everyman edition. London: J. M. Dent, 1994. 8-9)

To balance that, though, here’s my favourite quote about Bow Bells Novelettes, from G. K. Chesterton (who, among other things, wrote the Father Brown mysteries):

Nietzsche and the Bow Bells Novelettes have both obviously the same fundamental character; they both worship the tall man with curling moustaches and herculean bodily power, and they both worship him in a manner which is somewhat feminine and hysterical. Even here, however, the Novelette easily maintains its philosophical superiority, because it does attribute to the strong man those virtues which do commonly belong to him, such virtues as laziness and kindness and a rather reckless benevolence, and a great dislike of hurting the weak. (197-98)

(G. K. Chesterton’s “On Smart Novelists and the Smart Set,” from Heretics. 1905. London: Bodley House, 1950. 196-215.

I can’t argue with that.

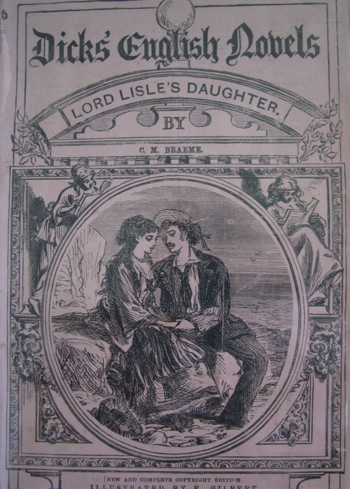

On a final note, it was not until I saw Bow Bells Novelettes in its paper covers (instead of bound in green cloth, as was usual for the yearly volume) that I realised how consistent John Dicks’s branding was across his various publications.

Look, for example, at this cover from C. M. Braeme’s Lord Lisle’s Daughter in Dicks’ English Novels (which reprinted novels to which Dicks had the copyright, mostly serials from Bow Bells or Reynolds’s Miscellany):

(Another Frederick Gilbert illustration.)

I don’t know if there’s anything significant about consistent branding: it did strike me as intriguing for late-nineteenth-century publications, though.

Share your thoughts