Magical Mystery Bookshelf Tour Stage Four: The Spare Room

Posted 16 July 2008 in Books by Catriona

I had thought to move on to the living room after the hallway, but I have a feeling I should get the spare room over and done with: it’s a disaster area.

To be fair, the spare room is home to a couple of our more specific collections, namely Nick’s art books and my girls’ school stories, which are the books I’m dealing with below.

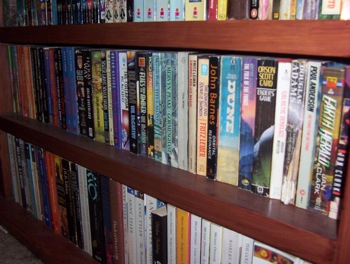

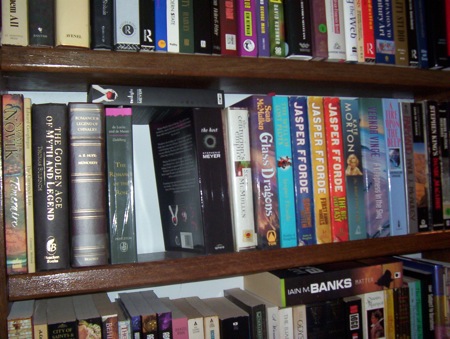

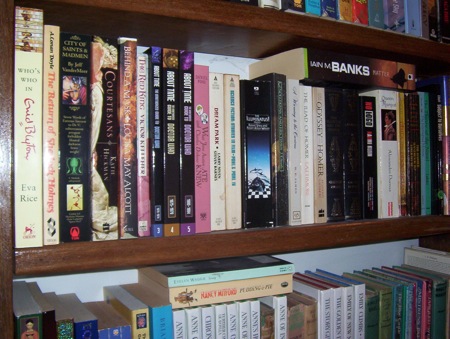

But it’s also the place where we store books that we have no other space for (namely, everything I’ve bought in the last eighteen months or so) or that we don’t re-read very often (like Nick’s New Adventure and Missing Adventure Doctor Who books). Almost every shelf is double-stacked to some extent, and finding anything is a nightmare.

(Actually, I thought my Seamus Heaney translation of Beowulf—which I still haven’t found—was bound to be in there, but I couldn’t locate it. That doesn’t mean it isn’t in there, of course.)

So the spare room it is, but it will take a while: there are five bookcases in there, all heavily stacked.

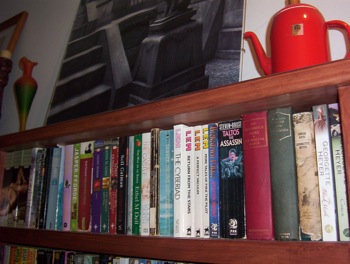

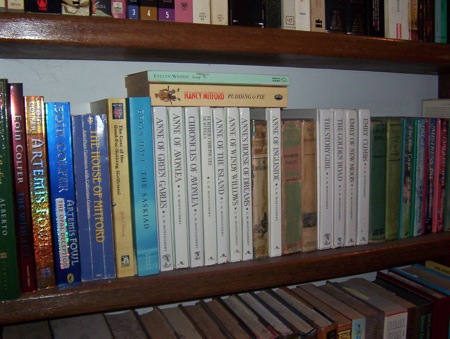

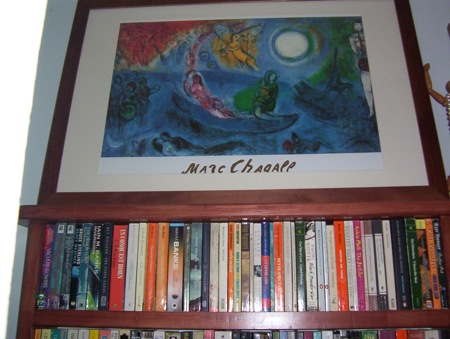

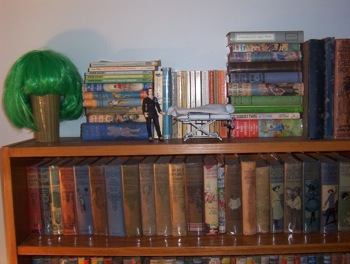

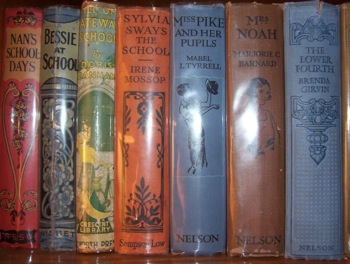

But I’m starting with a small shelf, one of the few shelves to be limited to a single genre: girls’ school stories. It’s largely impossible to make out specific titles, but that’s fine. After all, many of the books are completely interchangeable in terms of plots and characters. Plus, I’ve added some close-up photographs, for reasons that should become apparent.

Yes, that is a bright-green wig in a fetching 1960s’ style bob over that flower vase. How I come to own one of those is a long and not very interesting story. Still, it makes an interesting objet d’art, in its way.

Nick’s X Files figurine, on the other hand, led to the following conversation the first time my parents came to stay with us:

MAM: What’s that on the bookcase?

ME: Alien corpse. Why?

(And if you think that’s geeky, bear in mind that this is only one of a matched pair of bookcases: the other one has, in relative positions, a baseball cap with a propeller on the top and a figurine of Deanna Troi.)

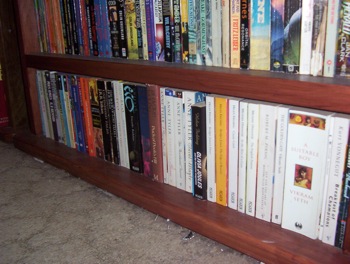

Really, though, the top of this bookcase just shows that these books are outgrowing the small space I allocated them, even though I haven’t been actively seeking to increase the collection in recent months. (I think part of the problem is that there were so many girls’ school stories published: it’s almost impossible not to find them in bookstores and sales.) I found an old photograph recently, when we’d first moved into the house, and there were only enough of these books for a single shelf: perhaps that’s evidence that I do need to keep a grip on my avarice?

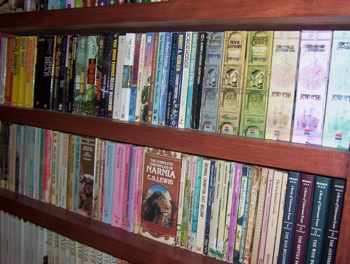

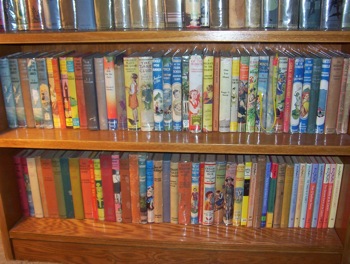

Even though I say the books are more or less interchangeable, those paperbacks standing upright on the bookcase’s top are some of the most sought-after among girls’ school story collectors: the Chalet School series. Obviously, these are inexpensive reprints (mostly Armada paperbacks from the 1970s) not collectors’ editions, but the series itself is one of the most heavily collected, along with the Abbey School series two shelves down.

The Chalet School series ran for decades in the hands of Elinor Brent-Dyer: Wikipedia lists fifty-eight books by Brent-Dyer from The School at the Chalet (1925) to Prefects of the Chalet School (1970)—Brent-Dyer herself died in 1969— as well as eleven books by other authors that slot into the original series, and Merryn Williams’s Chalet Girls Grow Up (1998), which, they carefully point out, is not recommended for young readers, and caused enormous consternation among Brent-Dyer fans because of its representation of infidelity, suicide, and marital rape among characters from the original series.

(Actually, if you have time—and are interested—the debate about Williams’s book on the U. K. Amazon site is fascinating.)

The Chalet School books themselves are intriguing, although often in a disturbing way. I was fascinated, initially, by the discrepancy in numbers between English girls and local students in the school, by the fact that English was not the dominant language in the school, and by the focus on Austrian culture. And the late Austrian books, with the increasing encroachment of Nazism, both in terms of actual soldiers and in terms of the spread of Nazi ideology among German and Austrian students, were genuinely distressing.

But then the school moved the Guernsey (after the Anschluss in 1938), then to the England-Wales border, and ultimately to Switzerland in the 1950s. With World War Two, the school shifted noticeably to a more uniformly British institution, and by the time they moved to the Swiss Alps, the tone was more reminiscent of the Enid Blyton-style “teaching foreign students the English code of honour” approach than it was to the tone of the early books. I found that a shame.

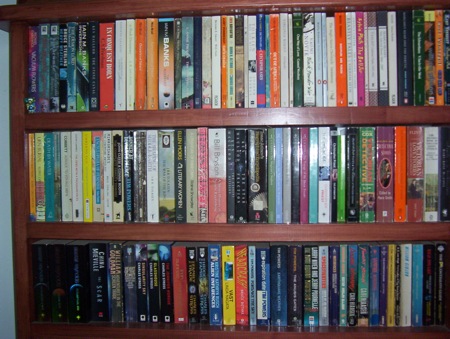

Ah! There are the Abbey School books, on the top shelf to the far left. This isn’t nearly as extensive a series: thirty-eight books, from The Girls of the Hamlet Club (1914) to Two Queens at the Abbey (1959), although Elsie J. Oxenham was extremely prolific outside this series, as well.

These aren’t always school stories, strictly speaking: many include the term “Abbey School” in their title, but so few of them take place explicitly at school that they’re often referred to as the Abbey Series.

But they have two fascinating points. The first is Oxenham’s involvement in the revival of English folk dancing (which is also an element of early Chalet School books, but falls away fairly quickly). I have no idea how accurate the details are, but the accounts of folk dancing are extraordinarily detailed, right down to music and steps.

The second is the Abbey itself: two of the primary characters are cousins, one of whom inherited a manor house and one a ruined abbey. It’s the Cistercian abbey of Grace Dieu, which my sister-in-law (whose specialty is Cistercian nuns) tells me is an actual abbey. Reverence for the abbey is threaded through the books—which also foreground Christian faith far more than most school stories—including a focus on the daily lives of monks in an order far less prominent, to the average reader, than the Dominicans or the Franciscans. It may only be a hook to drag in new readers, but it’s fascinating.

More so, certainly, than your average Enid Blyton (which are on the bottom shelf at the far right), although I own to a sneaking interest in the construction of Whyteleafe school in the Naughtiest Girl series (which is also the basis of my favourite in-joke in Green Wing.)

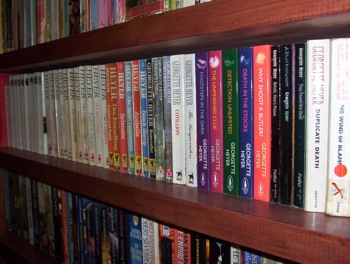

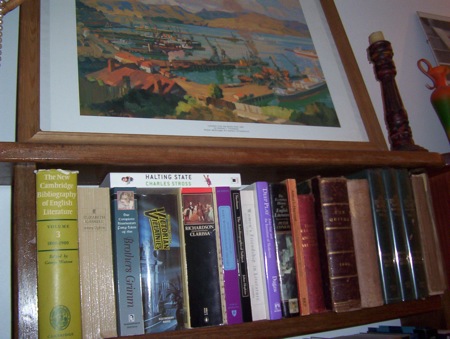

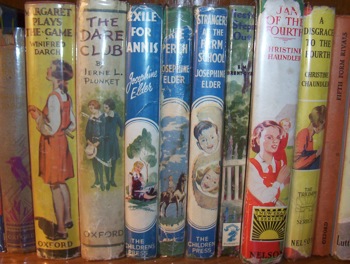

But what I love most about these books is their sheer beauty:

They’re just gorgeous to look at; Jan of the Fourth, there, was the first one that I bought in this new cycle of collecting (back in 1999), and I bought it purely because I loved the original dust cover.

And look at Margaret Plays the Game! Although that one is interesting textually, as well; it’s written as a schoolgirl version of a Sir Walter Scott novel that the six-form girls are acting out, in a truncated form, as the end-of-year play, and the association between Scott’s nineteenth-century rewriting of mediaeval codes of honour and the codes of honour pertaining among schoolgirls is intriguing.

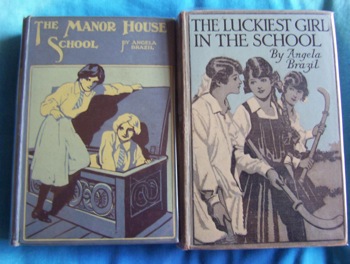

Even the ones that have lost their original dust covers are beautiful objects:

In fact, those two on the far left were part of Nick’s inspiration for the design of this site.

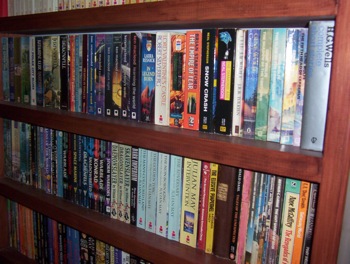

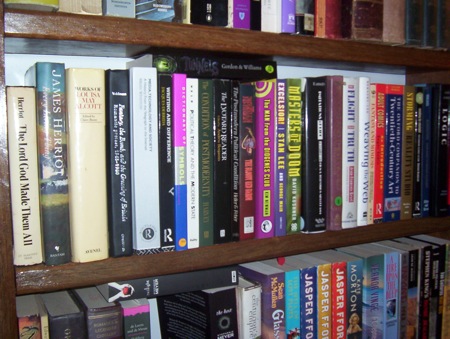

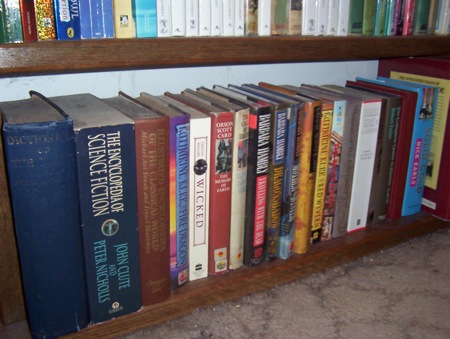

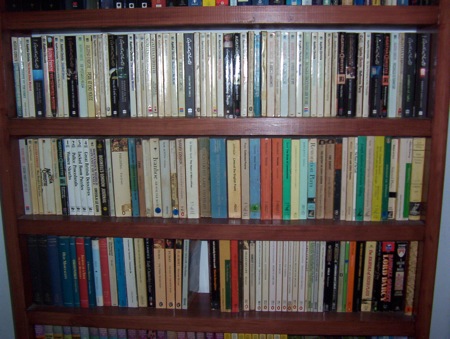

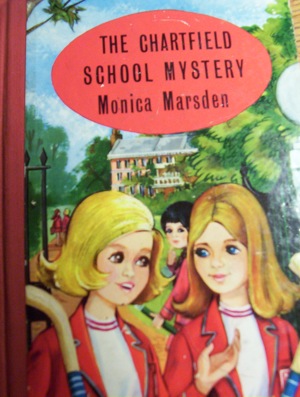

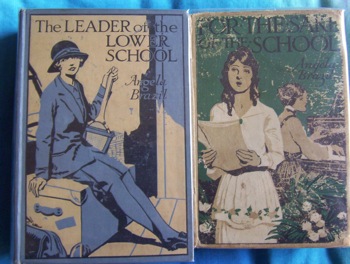

But if you want real beauty, you have to look at the covers of early Angela Brazil editions:

These are so stunning that it’s a shame I can’t display them with their covers facing outwards rather than their spines. Although they don’t always reflect the contents: Leader of the Lower Fourth is about a rather bolshy lower-school girl who doesn’t see why the upper school should run everything and organises a revolution among the younger girls, while the singer on the second cover is a rough-mannered New Zealand girl who is gradually civilised, apparently through some magic in the English air.

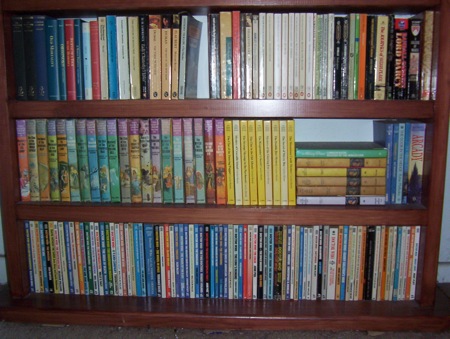

And it wouldn’t be a post on school stories if it didn’t end on a thoroughly bizarre note:

Why are those two girls climbing into a trunk? No idea. But don’t tell Matron!