Fictional Characters Whose Deaths Annoy Me

Posted 26 February 2009 in Books by Catriona

Warning: this is necessarily spoileriffic. I can’t help that, given the subject matter. But none of the books mentioned in here were published in the past ten years, and few in the past fifty years, so they’re spoilers of the most minimal nature.

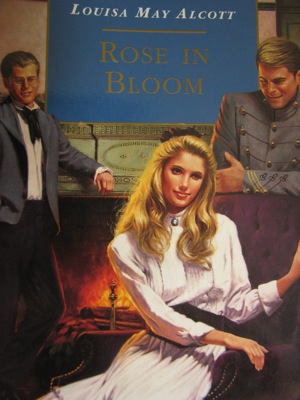

‘Prince’ Charlie Campbell, Rose in Bloom, Louisa May Alcott (1876)

If there’s one thing that drives me nuts, it’s when a character is killed simply so that an author can have a moral to a story.

Generally, they’re the most interesting characters, too: they’re not just hanging around being saintly all the time. (When such a character dies, it always reminds me of Montgomery’s Anne of the Island, where Anne writes “Averil’s Atonement” and is not-so-secretly furious that everyone prefers the villain to the hero, because at least the villain isn’t always just mooning around.)

So Prince Charlie is the victim of Alcott’s lifelong passion for the Temperance Movement. Because Charlie, you see, likes a drink.

I don’t think that Alcott is seriously arguing that if you like a drink you’ll end up coming home from a party absolutely off your nut; either forget about the steep embankment, or fail to see it because the lantern has blown out, or have something spook your horse; fall down the embankment with your horse on top of you; lie there all night in the freezing cold with severe internal injuries (and with a horse on top of you); and eventually be dragged out to die slowly and painfully in front of all your grieving family.

But that’s what happens to Prince Charlie. And all because he liked a drink.

Of course, one of things that annoys me most about this death is the reaction of Charlie’s mother Clara, who consoles herself with the fact that her mourning is very becoming.

She wasn’t nearly as annoying, shallow, and implausible a character in the first book, Eight Cousins (1875). She was still daft and self-centred, but at least she originally loved her son.

Dan, Jo’s Boys, Louisa May Alcott (1886)

Poor Dan. Another victim of an author’s need to kill people off in order to underscore a moral.

Dan turns up at Plumfield, the progressive school for boys (and two girls) run by Jo and Professor Bhaer, partway through the previous book, Little Men (1871). He’s brought by Nat Blake, who is one of the charity boys at the school (the school being a mixture of an expensive boarding school for the sons of gentlemen and a charity school to which poor boys can be admitted. The high fees paid by the former cover the cost of the latter, apparently—but we see few charity boys at Plumfield).

The charity boys are both failures, but Nat is a sympathetic and rather weak failure, so he’s allowed to marry one of the daughters of the house and to prosper.

But poor Dan.

We know nothing of Dan’s background, save that he’s been taking care of himself on the streets since an early age. He swears, he smokes, and he fights: his strengths are predominantly physical and he’s uncomfortable in the constrained atmosphere of the school. Eventually, he’s removed to a distant farm where difficult students are sometimes sent: he runs away from there and eventually makes his way back to Plumfield with a badly broken foot. The moment represents an awareness on both his and Jo’s parts of how much they care for one another.

In Jo’s Boys, then, Dan is one of the former students who regularly returns to Plumfield to seek the company and affection of Jo. He’s still physically imposing and impatient of restraint, but he’s intelligent and has a strong social conscience, particularly with regards to the mistreatment of the native American population.

Then he kills a man.

It’s an odd scene, because Dan, travelling out west, becomes aware that a very young and naive fellow traveller is being systematically fleeced by card sharps, and sets himself up as the boy’s guardian, standing and watching the games. When it becomes apparent that the men are cheating, he challenges them, one attacks him, and Dan, in reacting, knocks the man over, causing him to hit his head and die.

He’s charged with manslaughter, not murder, and serves one year.

But this is the unforgivable sin to the people at Plumfield. Never mind the accidental nature of the death, never mind the fact that Dan saves multiple lives through an act of extraordinary bravery shortly after his release from prison, never mind the fact that this is essentially a reprise of an incident with Amy and Jo in Little Women, except that Amy doesn’t die—Dan is cast out.

Oh, there’s weeping and wailing, and he compounds his sin by falling in love with a woman outside his social class—Laurie and Amy’s daughter, Bess—though he never tells her how he feels.

But, essentially, Dan is cast out from the only home he’s ever known.

Of course, Jo’s Boys is an odd book, anyway—with the deaths of Alcott’s mother (in 1877), youngest sister (in 1879), and brother-in-law, the autobiographical feel of the first books gives way in this to a kind of elegiac wish fulfillment, with all the family drawn together in a utopian compound of big houses and little, of schools and colleges, with even those who are dead memorialised in paint and marble and looking down over all.

And what’s poor Dan left with?

Dan never married, but lived, bravely and usefully, among his chosen people [native Americans] till he was shot defending them, and at last lay quietly asleep in the green wilderness he loved so well, with a lock of golden hair upon his breast, and a smile on his face which seemed to say that Aslauga’s Knight had fought his last fight and was at peace. (Children’s Press, p. 156)

Poor Dan.

Walter Blythe, Rilla of Ingleside, L. M. Montgomery (1921)

Just as Charlie and Dan are sacrificed to show the dangers of various vices or failings, Walter, I think, is sacrificed to show that war costs lives.

To be fair, none of the other members of the social circle to which the Blythes belong emerge unscathed, except perhaps youngest son Shirley—and Shirley is a strange non-entity in the books, never getting a chapter of his own in any of the later novels devoted to the Blythe children, never seemingly having any friends or sweethearts, never even being the focus of a paragraph that I can recall.

So why doesn’t Shirley die, instead of poor Walter? Walter, the poet. Walter, the scholar. Walter, the handsome child who doesn’t resemble any of his kin. Walter, the child gifted with a strange second sight that sits uncomfortably with the overall realism of the novels. Walter, the man who has to overcome a crippling terror of the horror and pain and despair of the Front to enlist and as a soldier, and who does so—only to die at Courcelette with a bullet through his heart.

If it had been Shirley, chances are no one would have noticed.

Balin, sometime before the events of The Fellowship of the Ring, J. R. R. Tolkien (1954)

Don’t ask me why Balin is my favourite dwarf in The Hobbit. He just is. And, yes, I know the dwarves are basically interchangeable, except for Thorin Oakenshield. But Balin is my favourite anyway.

So the point at which they find Balin’s tomb in Moria is the point at which I gave up The Lord of the Rings. (On my first reading, anyway. I have given up much earlier on subsequent readings, but I’ve never gone past Balin’s tomb.)

I am willing to admit that this might be the strangest thing that I have ever done.

Almost any character who dies in a David Eddings fantasy novel

But not for quite the same reasons. Dead characters in David Eddings’s fantasy novels are like dead babies in Victorian fiction: one is surprised not that it is done well, but that it is done at all.

No, wait: wrong quotation.

I mean that it seems as though the character is killed simply because it’s improbable that everyone should get through the adventures alive, so someone’s killed off in the later chapters, much as babies and children are killed off in Victorian fiction all the time not simply to reflect the real-life high infant mortality rate but also because, well, nothing’s quite as sad as a dead child, is it?

In The Belgariad (1982-1984), of course, the primary dead character is brought back to life almost immediately. In The Elenium (1990-1992), the dead character is the only working-class character in the book, which leaves me with an unpleasant sense that working class = expendable in Eddings’s universe. (Especially since in the trilogy that is the sequel to The Elenium, The Tamuli (1992-1995), there’s an undercurrent of “I know me place, young master” that seriously bothers me.) And in The Mallorean (1988-1992), there’s a prophecy that one of the questers will die, but when it happens, you’re left thinking, “Him? He was only mentioned in two paragraphs!”

It’s pathos by numbers.