I don’t normally link the articles on this solipsistic little blog to discussions in the wider blogosphere (though it sometimes happens almost accidentally, as with the season finale of Doctor Who).

But this is causing a little stir at the moment (courtesy of Crooked Timber): the owners of EndNote are suing George Mason University for an enormous sum over a tool (based on open-source software) that they say violates EndNote’s license agreement.

I’ve never been an EndNote user. I did try it, back in the days of my early enrolment in the M.Phil. programme: the library used to make it freely available to research higher degree candidates, and I did install it.

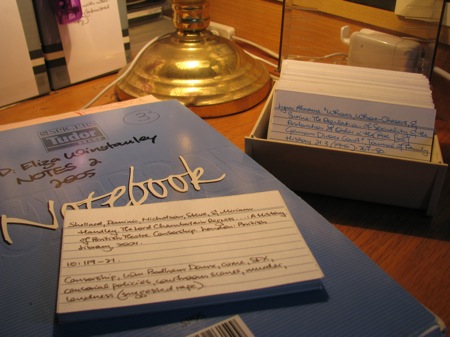

But it never suited me. My preferred bibliographical practice is this:

Index cards don’t suddenly crash in the middle of a project, they can be physically manipulated as a diagram of your argument, and they don’t suffer the same disadvantages as my other favourite research tool: Post-it notes.

(Those are forever losing their adhesive and ending up scattered all over the study floor.)

And yet, my most recent work had a strong bibliographical component.

The Ph.D. thesis required the standard list of works cited (a rigorous enough task—the standard academic requirements for accuracy aside—since established criticism on penny weeklies includes a large quantity of scattered pieces across a wide range of sources).

In addition to that, though, the thesis also included a second volume of scholarly bibliographies: the Index to Fiction in Fiction for Family Reading (1865-1866) and the Index to Fiction in the Second Series of Bow Bells (1864-1881).

This is a slightly different kind of bibliographical practice, of course, and not one to which EndNote is ideally suited.

But it is the reason why I’m peculiarly interested in bibliographical practice.

And, conversely, it’s why I’m concerned about what Crooked Timber points out as the side effect of this action against George Mason University.

While Fiction for Family Reading is only six volumes, the Bow Bells bibliography covers eighteen years—or thirty-four volumes or 882 (25-page) issues, whichever gives a better sense of scale. The entire 250-page index is the eventual result of six months in which I spent at least half of each day sitting in front of a microfilm machine.

That doesn’t seem relevant?

My point is this: an enormous amount of academic practice takes place in isolation.

Yes, collaborative work is an increasingly important part of academic life. But collaborative work is largely collaborative in the writing stage, not the research stage—and even then, it’s frequently a matter of independent writing followed by a stage of meshing different areas of expertise together.

It’s an important aspect of academic life. When I began my M.Phil., one of the main points they stressed for us was the importance of creating networks among other postgraduate students, of not spending three or four years scurrying between your office and the library and feeling increasingly isolated.

And this is where the apparent rival—in EndNote’s eyes—to EndNote becomes valuable: it’s not just a bibliographical tool. It also has a social-networking aspect, in that it allows academics to share, in Crooked Timber’s words, “metadata and other interesting things.”

As Henry points out on Crooked Timber, “this battle is likely to have long term consequences in determining whether or not new forms of academic collaboration are likely to be controlled by academics themselves, or take place through some kind of commercially controlled intermediation.”

Given that academic practice is already strongly skewed towards isolating work practices, this is a more serious concern than whether or not Zotero contravenes EndNote’s license agreement.

I’m rather pleased now that EndNote never suited me, although it would be satisfying to boycott it.

But that’s the point that concerns me here: I’ll leave the intellectual-property issues and the concerns about whether such a lawsuit is viable to those who better understand such issues.

Perhaps many years ago, when universities, at least on the European model, were largely staffed by academics who also lived on campus and therefore shared, to a large extent, a common social life in the common room, the isolating nature of academic practice wasn’t such a concern.

But that’s no longer the case.

And in the case of EndNote as opposed to Zotero, it’s dangerous to allow a commercially driven company to determine not only what type of bibliographical tool suits academics but also whether or not those tools should be used to foster collegiality.