I’ll be completely honest here: I have no particular hatred for David Eddings.

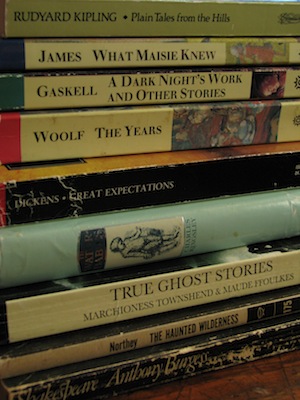

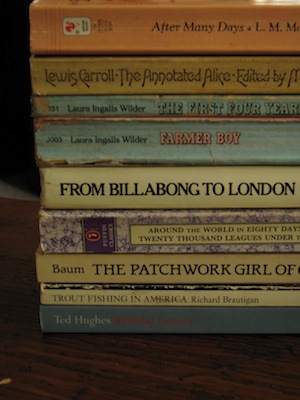

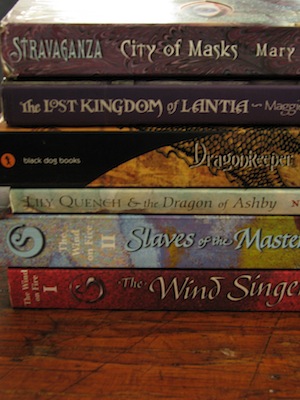

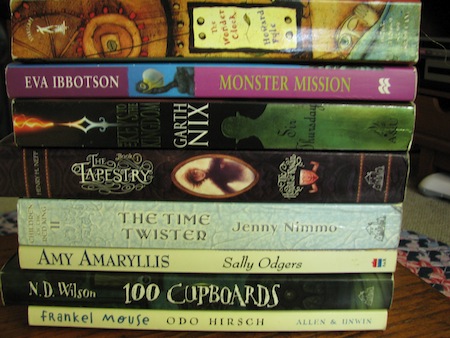

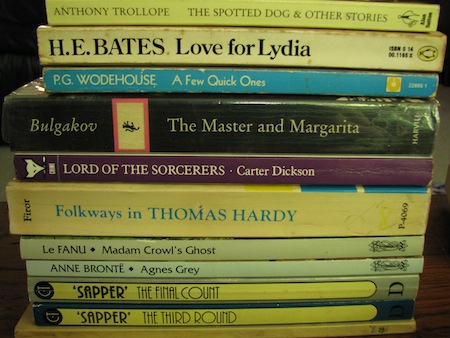

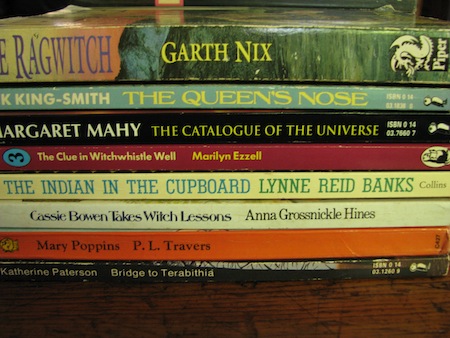

I first read Eddings in my early teens. I’d read many, many fantasy stories as a child, all the (cliche alert!) old classics: Alan Garner, Susan Cooper, Lloyd Alexander, Lewis Carroll, C. S. Lewis, Diana Wynne Jones, and so on.

But I’d slipped away from fantasy for a while, and I came back to it through David Eddings—to Nick, I call him “gateway fantasy,” though I know other readers who’ve done the same through Robert Jordan (whom I’ve never read) or Raymond Feist (whom I’ve never finished).

I read Eddings (specifically, The Belgariad) when I was staying with my best friend at her father’s house up on the Northern Beaches. She’d been reading them over a previous visit, so she lay on one bed with book three and I lay on the other with book one, and we worked our way through the series like that, reading the funny bits out to each other.

And they did seem funny, at the time.

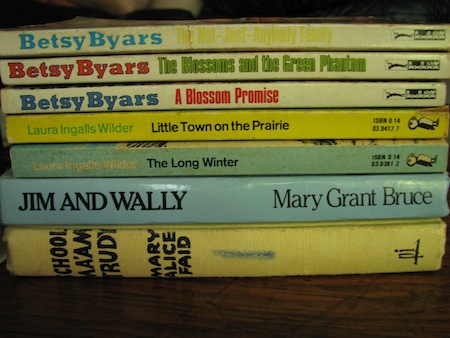

But the problem, for me, is that they don’t bear re-reading. I’m a big re-reader—hence this new series for the blog.

And Eddings doesn’t have any re-read value for me: when I re-read them over this Christmas break (out of desperation, since no one bought me any books for Christmas. Not one!), they just irritated me.

In fact, it was only sheer stubbornness that got me through The Mallorean, in the end.

So, do you want to know what really bothered me? And do you want it in list form? Of course you do.

1. Casual sexism

This is the big one, for me. Yes, there are powerful female characters in Eddings’s books, but their roles are severely restricted: they’re queens, sorceresses, witches, mystics, and priestesses. Not warriors. Rarely scholars. (And Eddings’s seeming contempt for academia is another big issue for me.)

They’re infrequently rulers in their own right and, when they are, they’re often ineffectual or powerless rulers like the drug-addled Salmissra.

There are some politicians, but they tend to manipulate their domains in much the way as they manipulate men. Because the sexism doesn’t just work one way in these books: women get their way by fluttering their eyelashes, and men are helpless to resist them.

It’s a wonder that anything ever gets done, really.

Somewhere in the depths of Polgara the Sorceress—though I can’t locate the actual page reference at this moment—Polgara mentions that she enjoys politics, but not in the sense of how kingdoms operate internally or externally. No, she likes politics according to the definition of politics that means (thought I’m paraphrasing here) “manipulating people into doing what I want them to do.”

But, then, if women understood politics, the male characters of The West Wing wouldn’t have anyone to info-dump on, would they?

I’m not even going to discuss the time that Belgarath says he’s jealous of his daughter’s suitors because all fathers are jealous—that’s just too Freudian and, frankly, creepy for me.

I wonder, too, why it’s necessary to protect the child-like Queen Ce’Nedra from any mention of anything to do with sex, when she’d been married for years and has a child. Yes, I agree you might not want your wife going into that brothel, Garion, but when it gets to the point where you can’t even mention in front of her that two secondary characters are lovers? Well, no wonder it took you so long to conceive an heir to the Rivan throne: it must be much harder when you can’t tell your wife what you’re doing.

But, you know, it’s not the sexism that bothers me so much as it’s the casual assumption of authority for the most dismissive and sexist of claims. So many sentences include some variation of the phrase “All women are” or “All men do” that you’re tempted to assume that, impossible though it is, the authors have never actually met anyone of the opposite gender.

I would write more on this, but when I got to the passage in Belgarath the Sorcerer where he apologised for calling his daughter extremely intelligent and then told her it was nothing to be ashamed of, my head exploded.

2. Casual racism

Actually, there’s nothing casual about the racism in these books, not when the plots are almost entirely driven by superficial but apparently extremely important racial differences. And while I’ve been drawing most of my examples from The Belgariad et al., this casual racism carries over into the later Elenium and Tamuli series, as well.

Add to that the general muddiness of definition between “race” and “culture,” and the whole angle of racism in the books becomes more confused. What we would often describe as cultural characteristics—such as the Arends’ overwhelming nobility—seem to be categorised as racial characteristics, which I find bewildering and just a little lazy. I’m also confused by how racial (or even cultural) traits work here: is it really possible for every single Arend to be as thick as two short planks? Every single one?

Still, the important point is this: for the life of me, I can’t figure out why it’s so important to the books that the bad guys are swarthy foreigners with almond-shaped eyes.

3. Casual cruelty

There are two key examples of this in the first hundred-odd pages of Belgarath the Sorcerer alone.

My first example is this: at one point just after Beldin—the deformed disciple of the god Aldur—arrives in the Vale for instruction, he’s telling Belgarath about how he was left exposed to die shortly after his birth, though his mother fed him until just after he learned to walk, when she either died or was killed by her people for sneaking out to sustain him. Thereafter, he learned to feed himself by following carrion birds and eating what they ate.

At which point Belgarath calls him an animal.

Well, possibly, Belgarath. Or possibly he’s a toddler who is trying to eat whatever he can find. Did you consider that possibility?

The second example is when Belgarath eviscerates an Eldrakyn (I’ve never been quite sure what those are, but something like an orc and something like a troll: intelligent creatures with the power of speech and the ability to domesticate other animals) and then laughs as the creature tries to hold its intestines inside its abdominal cavity.

But he feels “a little ashamed” when the creature starts crying, so that’s all right, then.

4. Idiot plotting

Here’s my favourite example: after the dragon-god Torak cracks the world in half during the War of the Gods, he is safe on the far side of the Sea of the East with Aldur’s Orb, his theft of which is the cause of the war. The people of the west spend two thousand years trying to cross the ocean before Cherek Bear-Shoulders and his sons find the land bridge.

But then they don’t cross the land bridge, because that’s the way Torak’s Angaraks will expect them to come. So they just walk across the frozen ocean instead.

I may have groaned out loud when I read that.

Was it a particularly cold winter? We’re not told that. But, then, the main characters do spend much of the books commenting on how stupid everyone else is. Perhaps that explains why crossing the ice never occurred to them in two thousand years.

Oh, but there are more examples. How about the fact that Chamdar the Grolim spends a thousand years searching for the heirs of Riva. He finally manages to get his hands on the newborn heir, burning the baby’s parents to death in the process. So this infant is the sole remaining heir of Riva—he will not have any brothers. He is the Godslayer whose rise Chamdar and his Grolims have spent a millennia trying to prevent.

But when Belgarath catches Chamdar at the burning house with the infant in his hands, Chamdar throws the baby at Belgarath so he can escape quickly.

No wonder it took him one thousand years to locate him in the first place.

On a sightly related note, I often wonder about the argument that since the books relate to two Prophecies (Eddings’s caps, not mine) divided by an accident in the distant past, the same events are going to keep recurring until one Prophecy is chosen over the other. Really, that’s just a retroactive explanation for why the plot of The Mallorean is largely identical to the plot of The Belgariad, isn’t it?

In fact, I know it is, because the characters keep pointing it out during The Mallorean.

5. Fondness for slavery

Do you know, I can’t even bring myself to discuss this, and yet it’s such a central part of his writing that I can’t delete the item, either. I’ll sum it up like this: even if slavery is codified within a society, it doesn’t necessarily follow that slaves are happy.

6. Confusing attitude towards racial purity

I think what confuses me most in Eddings’s attitude towards racial purity is that he places great emphasis on racial differences that are, at their heart, ambiguous. Take the Alorns, for example: four different peoples—Drasnians, Chereks, Rivans, and Algars—descended from Cherek Bear-Shoulders and his three sons.

The kingdom of Aloria was only divided into the four separate kingdoms three thousand years before the events of the main story, but that’s fair enough: even the descendants of full brothers can deviate widely after three millennia in vastly different climates. So we know the sneaky Drasnians differ from the silent Algars, the sober Rivans from the carousing Chereks.

But then at other times—many, many other times—characters will sigh “Alorns!” regardless of whether they’re speaking about Drasnians or Rivans, and the question of racial difference becomes muddied again.

Not too muddied, of course, because we have to remember that the bad guys are not of the same race as the good guys. That’s the important point.

And that’s not even considering how one keeps the line of the Rivan King essentially Rivan for one thousand years, when you’re marrying the various heirs off to Cherek, Algarian, or Sendarian girls constantly. Of course, with the exception of Sendars, those girls are all still Alorns, but the books don’t say they keep him Alorn; they say they keep him Rivan. The Rivan blood would become diluted after a short while, wouldn’t you think? Not that that’s a problem—unless you’re in a fantasy world obsessed with racial purity.

Of course, if I were to consider how the term “race” is apparently synonymous with “religion” in these books, we’d be here for the rest of the day.